"When we use language to communicate, we must choose what to say, what not to say, and how to say it. That is, we must decide how to frame the message." (Flusberg et al. 2024)

Any individual who has spent a reasonable amount of time studying combat aircraft has surely come across the concept of fighter generations. I am confident that most of my audience has as well. But, as prevalent as they are, fighter generations are a misnomer, and the continued use of the term has a negative impact on general understanding of jet fighter development and lesser-known aircraft.

The best place to start is by building an all-encompassing definition applicable to all fighter generations. However, this poses an immediate problem. There is no good, standardized definition of fighter generations. The term was first used to describe jet fighters in 1990 by Dr. Richard P. Hallion in Airpower Journal, but has come into its own due to the prevalence of the internet and the human tendency to categorize everything. For the purposes of this article I will be using a different, more familiar set of definitions, derived from three sources. First, a 2004 article on a website called Aerospaceweb, a different set of definitions from the Australian Air Power Development Center, and a similar set of definitions from a 2009 article in Air and Space Forces Magazine.

The History

Even before the Messerschmitt Me 262 entered service, several lines of jet fighter development had already begun across the globe. After the first jet fighter designs had been completed, work began almost immediately on advanced designs, applying the lessons learned from previous experience.

This became a pattern. As soon as a new design began production, it was very common for militaries to initiate design studies for the next fighter aircraft. This constant cycle of advancement applied to subsystems and other technologies as well, but mostly within companies at a proprietary level. Once an engine or radar design was finished, points that could be improved upon were identified and studies commenced to investigate potential improvements.

The rate of technological advancement was by far the fastest during the 1950s, as is evidenced from the rapid progression from the subsonic, straight-winged Northrop F-89 Scorpion's introduction in 1950 to the delta-winged, Mach 2+ capable Convair F-106 Delta Dart and McDonnell F-4 Phantom II of 1959/1960.

![Northrop F-89 Scorpion, Convair F-106 Delta Dart, North American F-86D Sabre, McDonnell F-101 Voodoo, Convair F-102 Delta Dagger and Lockheed F-104 Starfighter [1942x1552] - Imgur](/media/images/Northrop_F-89_Scorpion_Convair_F-106_Delta.max-1600x1600.jpg)

By 1960, development of new aircraft slowed as air-breathing threats were increasingly replaced by missile threats. With the introduction of the Convair SM-65 Atlas and the Soviet’s 8K64 (R-16/SS-7 Saddler) ICBMs in the early 1960s, the constant need for new, cutting-edge fighter-interceptor aircraft began to dwindle as the defensive focus shifted to missile and missile defense and defeat systems. However, technological progress did not stop. Additionally, the new advancements increased the average cost of new fighter aircraft, so Air Forces could no longer afford a new fleet every time that new technology allowed for improved performance.

This created a new stage in the progression of aircraft most akin to punctuated equilibrium, a concept from evolutionary biology. Charles Darwin believed the evolution of species was a slow, consistent accumulation of changes over time, the best of which led to improved survival. He called this theory phyletic gradualism. Eventually, close examination of the fossil record led biologists Niles Eldredge and Stephen Gould to propose a new theory called punctuated equilibrium. It posits that evolution is the product of a series of rapid changes in species induced by demanding new conditions. Both theories accurately describe different aspects of evolution and both concepts can be seen at work in the development of combat aircraft.

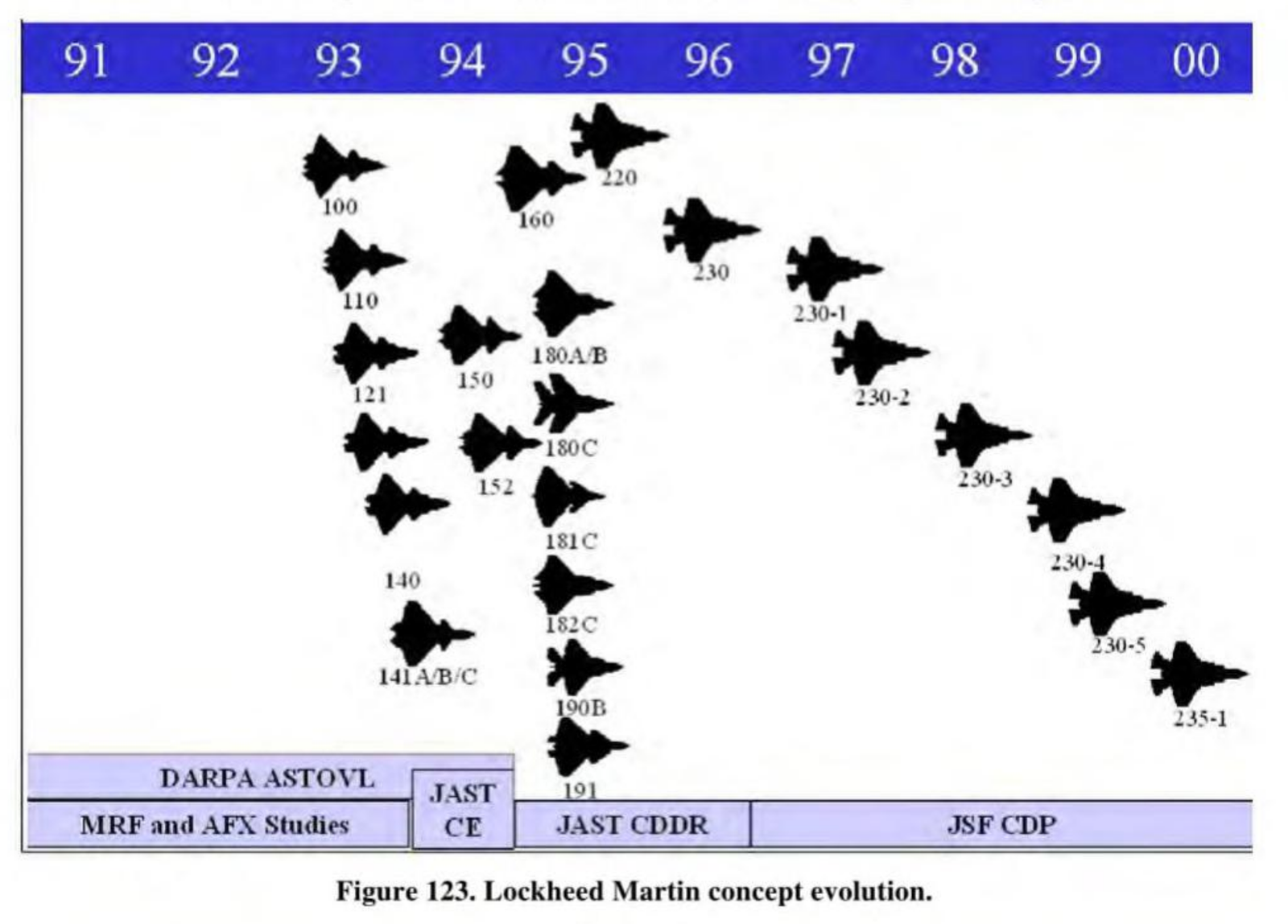

At the outset of aircraft development, countless design studies are conducted and designs are assessed for their validity. These studies are informed by prior experience, previous design studies, the requirements set forth for a program, and the technology available (or in development) at the inception of the program. A good example of this is with Lockheed Martin's F-35 Lightning II.

When the Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) program began, Lockheed-Martin's original design (Configuration 100) looked something more like a single-engine, canard-equipped F-22. One of the follow-on designs, Configuration 160, looked a lot like a smaller Chengdu J-20.

The JSF program integrated a number of technologies that had been developed since the F-15, -16 and -18, and program managers intended to integrate a number of technologies that were still in development, such as a Helmet Mounted Sight/Display (HMS/D). Technologies that were not yet ready, nor expected to be ready soon, were given a "technology readiness level" (TRL) benchmark to hit before they were considered mature enough to be integrated onto the aircraft.

As such, the F-35 shows up as a punctuational change in fighter design. The program drew conceptually from the F-16 program in many ways - by designing a lightweight, multi-role, relatively low-cost "Strike Fighter" while simultaneously integrating new technologies such as Low Observable shaping and coatings to create the free world's new favorite fighter.

The first aircraft to emerge from this new dynamic of "punctuated equilibrium" were the McDonnell Douglas F-15 Eagle and Grumman F-14 Tomcat, both developed through the late 1960s into the early 1970s and sporting much of the same technology as one another, but with very different mission parameters. These were faster than the previous group of fighters, with a longer combat radius, and long range, pulse-doppler "look-down/shoot-down" radars and missiles.

These aircraft featured many new technologies, but these were mostly the result of gradual evolution. It was not until the General Dynamics F-16 Fighting Falcon and McDonnell Douglas F/A-18 Hornet that one of the major revolutionary technologies of the 1970s would appear on fighter aircraft: digital fly-by-wire. While fly-by-wire experimentation began in the 1950s and analog systems had been implemented before, these two aircraft pioneered the implementation of a digital system.

Digital fly-by-wire allows inherently unstable aircraft to fly in a like-stable condition due to constant computer monitoring and automated adjustments, without requiring pilot input. This instability is exploited by the computer to greatly enhance maneuverability. This changed the way fighter aircraft were designed to meet the same goal. Now designers could make an unstable, highly maneuverable aircraft without the risk of the pilot losing control.

However, this seemingly sudden advancement in technology and capability between the F-4 and F-106 to F-14 and F-15, and on to the F/A-18 and F-16 was really just the application of technology that appeared in the interim into new fighter designs. Advancements we see in new airframes are a punctuational change in the equilibrium, but not a break in the continuity of development, as is implied by a new "generation".

This appearance of an evolutionary leap was clearest on new aircraft designs, but examples of the continuity of development even across a single airframe are widespread. Two good examples of this continuity can be found in two variants of 1960s naval fighters, the F-4J and F-14D.

The F-4J was the first in-service aircraft with a pulse-doppler radar in the form of APG-59. This meant that the F-4J could find targets below it that may be obscured by ground clutter. Despite the F-4 Phantom's design being a few years old by the point the F-4J arrived in 1966, the increased range and capability of the new radar set was a critical advantage over every other combat aircraft that existed to that point, despite only being marginally useful in Vietnam.

With a few modifications, such as Pilot Lock-on Mode(PLM) and Sidewinder Expanded Acquisition Mode(SEAM), Naval Aviators who flew the F-4J of the mid-1970s flew one of the best air superiority fighters of the era, a wholly different machine from the interception-focused F-4B introduced in the early 1960s.

The F-14D's introduction was years removed from the F-14A of the early 1970s, and the technological advancements that came with it were staggering. The new APG-71 radar, derived from the F-15E's APG-70, was more powerful, more reliable, more jam-resistant, and offered new air-to-air and air-to-ground modes that outperformed anything else in inventory.

The F-14D featured new, more powerful and reliable engines, a new infrared search and track system that nearly reached the range of its radar, advanced digital Electronic Warfare (EW) equipment, and more. Had the Cold War not ended, the F-14D would likely have seen another decade or two of service before being replaced, considering the significant advancement in its capabilities.

These are both examples of major advancements in capability advancements through continuous development and application of new technologies, yet neither are considered a new "generation." Why?

The Problem

The problem of "generations" as definitions requires an explanation of how the language we use to describe different groups of aircraft impacts our perception, as well as a review of the definitions themselves.

As has been shown in countless studies, language and framing heavily impact the perception of anything delineated by definitions. "Generation," by definition, collectively refers to people born and living around the same time, generally about 20 years. Often associated with a defined generation are shared formative experiences of that era, such as major world events, media, music, culture, and more. It is also assumed that the majority of people of that generation share similar attitudes and characteristics. As an extension, there is also an assumption that a majority, or all of the members of a given generation share similar characteristics as well.

However, recent studies have shown that there is little scientific basis for these distinctions, and aside from their role in family trees, and that the concept of generations serves very little practical purpose. Indeed, the broadly general concept of different human generations is often misused as an easy substitute for deeper analysis.

The situation with fighter jets is much the same. Though the concept of fighter generations originated with Hallion in 1990, the definitions found on Aerospaceweb appear to have become the de-facto set of definitions found in most modern discussion. These definitions have a number of problems. They, like human generations, have characteristics and traits associated with them alongside the temporal component, which negatively impacts our perception of the history of fighter development in that era.

To demonstrate these issues, I'm going to use a few case studies of aircraft that do not fit into the generations that people often put them into.

The Lockheed F-104 Starfighter was designed based on feedback from pilots who fought during the Korean War that struggled against MiG-15s in combat. It was revolutionary at the time, a step away from complicated cockpits and fiddly radars, with simple, easy-to-use controls and a simple radar, high maneuverability at speed, with an internal gun and the Sidewinders it carried on its wings as its main armament. It was simple to produce and maintain, reliable, durable, and powerful. Later versions of the Starfighter incorporated robust air-to-ground capabilities since the aircraft was so well behaved and stable in flight, especially so near to the ground.

This mentality and description sounds a lot like what was said about the F-16 that replaced the F-104 in the export market, and this is right. Both the F-104 and F-16 were air combat focused day fighters. The concept of a "day fighter"(a fighter with simple radar, no radar-guided missiles, and designed for within-visual-range combat) is far older than the "all-weather fighter" concept (a fighter with a complex or powerful radar, with radar missiles that could be employed at night or in infrared-obscuring weather) that would eventually replace it.

The F-104 is often just seen as an interceptor, due to its "second generation" label, high speed, and small wings. This was compounded by the F-104's poor service and high accident rate in West Germany, which was primarily due to the F-104's difficult low-speed handling and a complete lack of supersonic conversion training for pilots at the time. Other nations in Europe used it with relatively few fatalities and with great success.

Let’s look next at the Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-23. This iconic Soviet aircraft was designed to incorporate maneuverability equivalent to the early MiG-21s of Vietnam War fame. The MiG-21 was a day fighter with little to no room for advanced electronics and radars, especially because of the nose-mounted engine air intake. However, the Soviets also wanted better takeoff and landing characteristics than the MiG-21. Thanks to General Dynamics and Grumman proving that variable sweep wings could work, TsAGI (Soviet Central Aerohydrodynamic Institute) was able to push for the “swing wings” as a solution to the low-speed control problem without sacrificing any of the performance envelope.

Though the early variants would struggle with maneuverability, by the second-generation MiG-23 airframe, these problems had been mostly solved. The later MiG-23s put a much greater focus on maneuverability due to the increasing emphasis on dogfighting in the Soviet Air Forces during the 1970s.

MiG-23s featured an unusual but effective look-down/shoot-down radar rather than the "standard" pulse-doppler, a powerful turbojet engine offering a thrust-to-weight ratio of nearly 1, an advanced heads-up display, an infrared search and track system, and more. But they are generally considered third generation aircraft, rather than fourth, which is misleading because of their more advanced design.

The F-14 was designed primarily as an interceptor. It was to fly a patrol at a distance from an aircraft carrier, with the ability to sprint up to high speeds to intercept Soviet Naval bombers before they could reach weapons release against carriers. This was the primary role that it inherited from the General Dynamics F-111B Aardvark. It was to take over for the F-4 eventually, so maneuverability and dogfighting capabilities were important in the F-14's development. But not at the cost of interception performance.

While the F-14 was more maneuverable (and far better optimized as an air superiority fighter) than the F-111B, it carried (almost) the same engines, the same radar and computer suite, and many of the same speed and range requirements as the F-111B. It was similarly filled with solid-state analog systems mixed in with rudimentary microprocessors such as the MP944.

The F-14 fits well into neither the category of third generation nor the category of fourth generation. It has "features" of both, from its interception focus to its bubble canopy for better vision and its powerful pulse-doppler radar.

While these three examples all show demonstrate different shortcomings of the fighter generation classification system, one common thread remains. Generations, in practice, are used to describe aircraft with loosely equivalent combat performance, often based around loose generalizations of technological level. In applying these labels, we indirectly apply assumptions about development, purpose and capability that are often misleading or completely incorrect.

The effect it is describing is just a rapid advance, a leap in evolution, but the term "generation" implies an overhaul or revolution in theory and technology during fighter development. There is no such paradigm shift. It only appears that way because the public is rarely exposed to the countless design studies that go into development of a modern aircraft, so they do not see the gradual change.

Finally, aircraft that were advanced for their time in concept or technology are often forgotten due to a general assumption that they just "fall into the same category" as aircraft of their same "generation."

The Solution?

One could easily argue that our current perception of fighter generations is just a marketing term that has gotten out of control. The easiest and best solution to this problem is to stop using the term "fighter generations" altogether. And, for most of you who have made it this far, this is what I suggest you do. Read about aircraft and their development history from good sources, learn about their technical capabilities, and analyze aircraft's relative performance at an individual aircraft variant level.

This does not, however, provide a good solution for those less inclined to do that kind of in-depth research. There are benefits to the system as it is commonly used by the general population, such as comparing types of aircraft with dissimilar technology levels and capabilities.

My proposal below is an imperfect solution with aircraft that will no doubt not fit into my own categories. Thus, I want to open this to the audience. Do you have a solution? Email me at sam@greatdefensesite.org with your ideas and I will display the best of them below or on another page.

My Solution

My proposed solution is to use "groups" to define aircraft by roughly equivalent technological levels. This provides a simple alternative to "generations" that does not carry the same connotations. Additionally, different variants of the same aircraft can change "groups" based on upgrades, if they are significant enough.

Some major distinctions must be made before groups can be defined. As mentioned earlier, there is the distinction between day fighters and all-weather fighters. Day fighters were the most common type of fighter until the late 1950s and early 1960s, when radar and radar-guided weapons were sufficiently advanced to practically apply to air superiority fighters. The concept continued to exist in limited fashion until the late 1980s, when the F-16A/B design was finally replaced with the F-16C/D Block 30/32, which added the ability to carry AIM-120 AMRAAMs, making it an all-weather fighter.

The differentiation between day and all-weather fighters is critical because of the difference in technology that they have. Therefore, groups must have distinctions between day and all-weather fighters, as "Group x-D" and "Group x-AW" For groups one through three, day fighters will be assumed to be the "default type" of fighter, due to their prevalence. After group four fighters, the default assumption will be that the group refers to all-weather fighters unless otherwise specified by mention of day fighters or use of the -D suffix. There are no day fighters after group six.

Equally, the differentiation between very low observable (VLO/stealth) and upgraded airframes becomes important around group eight and nine, where technological levels are equivalent, but stealth airframes are notably more capable. These will follow a similar format to the all-weather and day fighter differentiation. Starting with Group eight, groups will be split between "Group x-S," referring to VLO designs, and "Group x-NS," referring to upgraded legacy designs without significant signature reduction or other new non-VLO designs.

Group 1 is the first group, and refers to subsonic fighters with generally straight wings and poor transonic performance. These were developed from the beginning of jet fighter development to the end of the 1940s.

- Group 1-D examples

- P-59 Airacoment

- Me 262 Schwalbe

- F-80 Shooting Star

- F-84 Thunderjet

- MiG-9

- de Havilland Vampire and Venom

- Gloster Meteor

- Group 1-AW examples

- F3D Skyknight

- F2H-3/4 Banshee

- F-89 Scorpion

- CF-100 Canuck

- Gloster Meteor "NF"

Group 2 aircraft generally incorporated better transonic aerodynamics and handling characteristics, as well as more powerful engines, occasionally including early afterburners. These were developed mostly from the end of the 1940s to the mid-1950s, and did not reach much above Mach 1, if at all. Simple air-to-air missiles began appearing at this time.

- Group 2-D examples

- F-86 Sabre

- MiG-15/17

- Dassault Mystère IV

- Hawker Hunter

- F11F-1 Tiger

- Group 2-AW examples

- F-86D Sabre Dog

- de Havilland Sea Vixen

- F3H Demon

Group 3 aircraft are early Mach 1+ capable aircraft, but before transonic aerodynamics were well understood, so many of them are inefficient. These were mostly developed in the early 1950s to late 1950s. Many of these aircraft incorporated early air-to-air missiles during development or early in service.

- Group 3-D examples

- MiG-19 (day fighter versions)

- F-5 Freedom Fighter

- F8U Crusader

- F-100 Super Sabre

- Su-7 (fighter versions)

- Group 3-AW examples

- F-101B Voodoo

- F-102 Delta Dagger

Group 4 aircraft were more capable Mach 1+ aircraft, reaching even beyond Mach 2. Some were designed for situations or roles they never found themselves in due to the rapid changes in air combat at this time. Air-to-air missiles were all but a requirement by now. Group 4 was the first of the longer categories, with aircraft entering service between the mid-1950s and the mid-1960s. All-weather fighters began to be more popular choices.

- Group 4-D examples

- MiG-21F-13

- F-104 Starfighter

- F-5E Tiger II

- Mirage III

- Group 4-AW examples

- MiG-21S

- F-106 Delta Dart

- F-4B/C/D Phantom II

- Su-15

- English Electric Lightning

Group 5 aircraft began to introduce advanced avionics features such as early look-down radars, monopulse radars, heads up displays, and onboard digital computers. By this point in time, all-weather fighters were beginning to be designed with day-fighter maneuverability mind, combining the advantages of both types of aircraft. These were introduced from the mid-1960s to the mid-1970s.

- Group 5-D examples

- IAI Kfir

- Group 5-AW

- Dassault Mirage F1

- F-4E/J/S Phantom II

- MiG-23M/ML

- F-14A (early blocks)

Group 6 aircraft are mostly comprised of what people normally consider "fourth generation" aircraft. Day fighters of this group made up for their lack of radar with eye-watering dogfight performance.

- Group 6-AW examples

- MiG-23MLD

- F-14A/B

- F-15A/C

- MiG-29 9.12/9.13

- Dassault Mirage 2000/2000C

- F/A-18A/B/C/D Hornet

- Su-27

- Su-30M2/MKK/MK2/MK2V

- Group 6-D

- F-16A

- YF-17

Group 7 aircraft are mostly designed around the same roles and lines as Group 6 aircraft, but are more advanced in technology. Most incorporate some level of RF signature reduction. There are some airframes in both categories.

- Group 7 examples

- F-14D

- Shenyang J-11B

- Su-35

- Su-30SM/SM2/MKI/MKM/MKA

- MiG-29M & MiG-35

- F-15E (later versions)

- Eurofighter Typhoon (early versions)

- Dassault Rafale (early versions)

- Dassault Mirage 2000-5

- F/A-18E/F Super Hornet

Group 8 aircraft distinguish themselves with lowered RF and IR signatures, modern "glass cockpits," advanced EW suites (often including DRFM jamming), and is once again split between two separate groups: "stealth"(-S) and "Non-Stealth(VLO)" designs (-NS)

- Group 8-S examples

- F-35

- F-22

- J-20

- J-35

- Group 8-NS examples

- F-15EX

- F/A-18E/F Block III

- Eurofighter Typhoon Tranche 4

- Rafale F5

- F-16 Block 70

- Su-57

- Shenyang J-11BG/15/16

Group 9 aircraft will likely have a high focus on VLO beyond what is in service today, but more importantly will have even more advanced onboard EW equipment, will likely work in tandem with autonomous combat aircraft, and will feature other yet-to-be-defined capabilities.

- Group 9-S examples

- F-35 (future upgrades)?

- F/A-XX

- NGAD

- JH-36

- GCAP

- FCAS

- Group 9-NS examples